Earn above 4.5% by investing in Money Market Funds

The information provided on this blog is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be construed as financial or investment advice. The reader should seek professional financial advice before making any investment decisions based on the information provided on this blog.

After the failure of US regional banks such as Silicon Valley bank and few other banks, investors have been pulling their money away from US banks to invest in Money Market funds. Initially much of that flow was driven by more attractive rates, but concern about the steadiness of some smaller lenders helped turbocharge that within the past month.

About $350 billion flowed into money funds in the four weeks ending April 5, according to the Investment Company Institute. That pushed assets to a record $5.25 trillion, topping the $4.8 trillion pandemic peak

.

What are money market funds?

They are mutual funds in a way that invest the cash in short-term, liquid instruments, including cash, certificates of deposit and US Treasury bills, and follow federal guidelines around quality, maturity, liquidity and diversification. They’re required be at least 10% invested in daily liquid assets and 30% in weekly liquid assets; the Securities & Exchange Commission is proposing to raise that to 25% and 50%.

They have maintained their price at $1 per share, and pay interest in the form of dividends. However, it is important to note that these are not FDIC insured, but they would lose their appeal if they trade below $1.

What are the returns on these?

Typically they pay closer to Fed’s effective fund rate which is currently at 4.83%. As an example, the Vanguard Treasury Money Market Fund (VUSXX) had a 4.70% yield as of April 5, compared with a 0.06% national average on interest checking accounts and 0.37% on savings accounts, according to March data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Even high-yield savings accounts have lower rates, with Goldman Sachs’s Marcus currently paying 3.75%

.

What are the fees on these?

It depends on the fund, but as an example Vanguard’s Treasury Money Market Fund (VUSXX) charges a mere 9bps (0.09%).

How are they able to pay a higher rate than banks?

Money funds are more nimble at passing on any changes to the Federal Reserve’s benchmark interest rate than banks are. Over 20 years, around 86% of changes in central bank interest rates flowed though to retail money funds, compared with 26% for retail CDs, according to a Federal Reserve Bank of New York blog post. Many banks take advantage of sticky deposits and are able to get away by not passing the higher rates they earn at Fed Facilities.

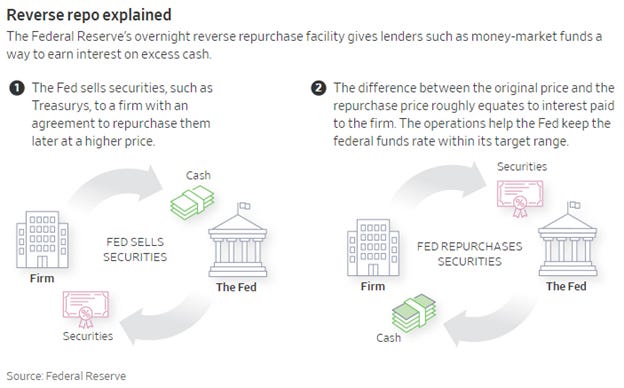

Banks and large investment institutions have access to Fed reverse repo facilities, allows financial firms and others to earn interest on large cash balances. As of Wednesday, more than $2.2 trillion sat in the Fed’s reverse repo facility, paying a 4.8% annualized rate. That is well above the rates on offer at most banks.

What is a reverse repo?

A reverse repurchase agreement, also known as a "reverse repo," is a financial transaction where the Federal Reserve sells a security to a qualified buyer with an agreement to buy back the same security at a later time for a specified price. The difference between the sale price and the repurchase price, along with the amount of time in between, determines the interest rate paid by the Federal Reserve for the transaction. Essentially, it's a way for the Federal Reserve to borrow money from qualified buyers, using securities as collateral, and paying interest on the borrowed amount. For more details see NY Fed website

What are the risks?

Let me start by quoting Brent Donnelly “Money market funds are an extremely safe and boring place to put your money. When yields are low, you don’t want your cash in money market funds, but at 4% or so, you could do worse!”

Money funds are subject to changes in interest rates, which can cause their yields to go up or down. It's important to note that they are not FDIC-insured, unlike traditional savings accounts.

Institutional prime funds, which invest in commercial paper, have historically been more vulnerable to panics. For example, in 2008, the Reserve Primary Fund had to reprice its shares below $1 after investors withdrew $40 billion in just two days due to its exposure to the commercial paper of bankrupt Lehman Brothers. In March 2020, institutional prime funds saw large outflows as the pandemic hit, and the Federal Reserve had to intervene to support short-term funding markets.

The recent banking crisis has also led to investor concerns about prime money market funds. For instance, Charles Schwab experienced $8.8 billion in net outflows from its prime funds in just three days in mid-March, while its own government and Treasury funds had inflows totaling about $14 billion on those same days.

How are money market funds preparing for a potential debt ceiling crisis?

I saw a very interesting article answering this question on Yahoo. Government officials and ratings agencies have expressed concern about the vulnerability of money market funds to stress. Fitch Ratings warned that Treasury-only money market funds may experience investor redemptions and volatility if investors believed the government were to default. Janet Yellen has also cautioned that money market funds are at risk of runs on deposits during times of market stress and has called for stronger regulation. In response, some portfolio managers are avoiding Treasury maturities that could see volatility around the X-date and are turning to the Fed's reverse repurchase agreement (RRP) facility for liquidity. The money fund industry has also established working groups to prepare for the possibility of a technical default by the Treasury.